The British royal family has released a statement saying that the Duke and Duchess of Sussex will keep plans for the arrival of their baby private. Other royal births have been announced almost immediately, with the new family posing for photographs soon afterwards on the steps of the Lindo Wing of St. Mary’s Hospital in London. Meghan and Harry, however, have chosen to “celebrate privately as a new family”, before placing their baby in the public eye.

As the London media speculates about when and where the birth will take place, the modern craving for instant information and “access-all-areas” insights has never been more apparent. Despite established privacy laws, information continues to spread, leak and diffuse – often without the subject’s consent. The fact that the Duchess had to make the request at all is, in itself, a telling sign.

Indeed, Meghan’s desire to retain privacy surrounding her impending birth has a historical precedent. The intimate – and largely lost – realm of the medieval “lying-in” room is a reminder that the modern predilection for publicising the deeply personal was not always the norm.

How long did you wait after the birth of your newborn before going out in public? Was your decision based on cultural or religious practices? Share your story with us, and we could publish your letter. Anonymous contributions are welcome.

A long lie-in

Most pregnant women in the middle ages were tended to by other women, during an extended lying-in period of around two months, before and after childbirth. This private zone gave expectant women the time and space to prepare for, and recover from, childbirth, while awaiting the moment they were permitted to re-enter the church, in the ceremony of purification after childbirth.

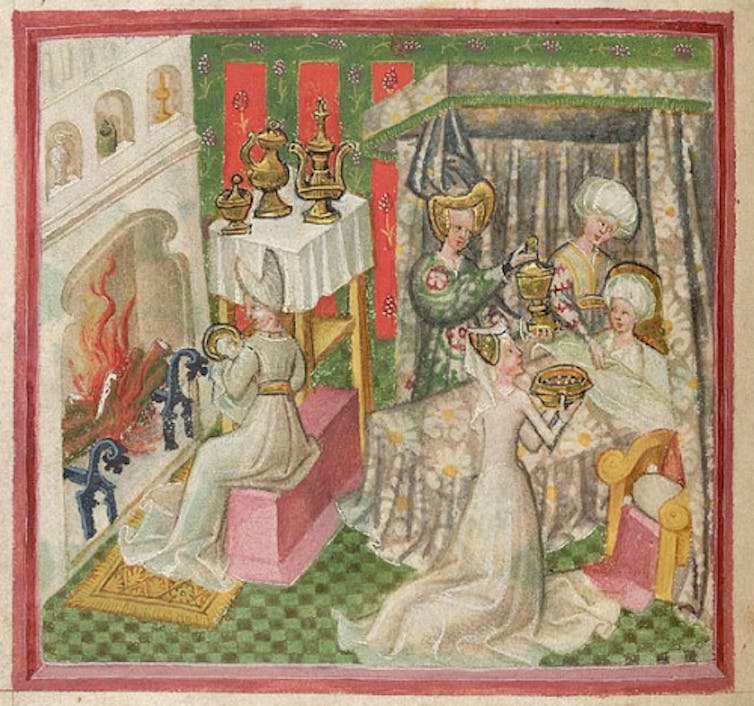

A 15th century manuscript miniature of the birth of St Edmund depicts the birthing chamber, midwives and female companions. The new mother rests in her bed as she is fed, made comfortable and soothed with aromatics by the women who care for her, while the baby is warmed before the fire.

The lying-in room was a womb-like space, adorned with tapestries for privacy and warmth, with daylight limited often to a single window, and herbs scattered across the floor to create a pleasant scent with therapeutic benefits. Women of higher social status were often bestowed with brooches, pendants and books depicting icons of healing saints, as well as jewelled girdles and statues of female saints.

Painted birthing trays, or salvers – such as this desco da parto from Florence – were given to wealthy women after childbirth, to serve mulled wine and clean linens: a sign of the value bestowed on noble births. Though present in this depiction, men were rarely permitted to enter the lying-in room – entrance was by invite only, through the monitored doors.

Wandering wombs

Childbirth was a dangerous business for mother and child in medieval times, regardless of their social station. Of course, royal births in the middle ages were different to those of peasant women, whose return to the hard labour of everyday life would demand a less luxuriant recovery period. But while aristocratic households could afford the services of university-trained male physicians, hands-on care remained the job of the midwife.

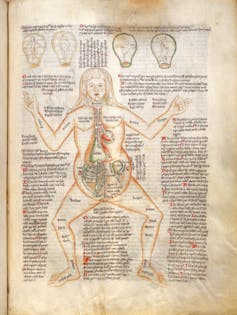

The medieval gynaecological and obstetrical handbook known as The Trotula ensemble contains instructions for midwives on how to deliver a baby safely. Medieval understandings of the female body included the ancient Hippocratic belief that a woman’s womb was like a living creature that “wandered” around her body – a stereotype of “unruly” women which still lingers today. The postpartum uterus was seen to be particularly disordered. The Trotula author notes:

The womb, as though it were a wild beast of the forest, because of the sudden evacuation falls this way and that, as if it were wandering. Whence vehement pain is caused.

Such notions of the “wandering womb” are manifest in images from medical manuscripts that show the uterus “floating” around the words on the page. These disembodied wombs show common foetal presentations, and a reasonably accurate knowledge of anatomy – surprising, in an age when human dissection was taboo and male physicians had limited access to women’s bodies.

Also see: IN PICTURES: What Prince William and Queen Elizabeth looked like as babies

Dragons and divination

The story of St Margaret, the patron saint of childbirth, was well-known to women in the middle ages. Margaret was swallowed by a dragon but, after making the sign of the cross, was expelled quickly. Her popularity reveals how an uncomplicated birth was desired just as much throughout history.

Just as our modern fascination at guessing the sex of newborn babies remains, various medieval techniques for predicting the sex of a baby abounded. This one from The Trotula requires some careful orchestration:

In order to know whether a woman is carrying a male or a female, take water from a spring and let the woman extract two or three drops of blood or milk from her right side and let these be dropped in the water. And if they fall to the bottom, she is carrying a male; if they float on top, a female.

It’s safe to say that Meghan and Harry are unlikely to try this at home. But these medieval practices show that – unlike Marie Antoinette’s hugely public birth in the 18th century – watched by a plethora of spectators after her obstetrician called, “the Queen is going to give birth!” – childbirth need not always be a public spectacle.![]()

Laura Kalas Williams, Lecturer in Medieval Literature, Swansea University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Chat back:

How long did you wait after the birth of your newborn before going out in public? Was your decision based on cultural or religious practices? Share your story with us, and we could publish your letter. Anonymous contributions are welcome.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners